The Ripples of War Are Only Beginning to Spread. Is America Ready?

Drop a pebble into a pond and, after the initial splash, ripples spread across the water. It’s a familiar image, one we know so intuitively that everyone understands immediately what you mean by the phrase “ripple effect.” Yet, even when the pebble is a boulder, and the splash soaks us, we may not fully grasp how far the ripples will spread—or for how long.

On March 20, 2003, the United States invaded Iraq. I crossed the berm two days later as part of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), 26 years old and full of equal parts naivete and cynicism. The war already seemed unjustified to me, but I felt deep loyalty to my fellow troops, and some measure of excitement at what was to come. If the waiting place is, as Dr. Seuss says, the worst place to be, I’d rather have been at war than sitting around Camp Udairi.

Kayla Williams crossed the berm two days after the March 20, 2003 invasion of Iraq as part of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). Photo courtesy of the author.

During my deployment, I went on combat foot patrols with the infantry in Baghdad, got bored out of my mind on Mount Sinjar, endured chronic sexual harassment, and came home feeling like America was a foreign land after a year in the Middle East. In Iraq, I also met the man who became my husband.

In retrospect, my book about his injury and our relationship was an effort to tell myself that the ripples had stopped spreading. We coped with his traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder, learned to navigate the Department of Defense and Veterans Affairs, and advocated for improvements to systems and services. I wanted a nice tidy narrative arc. I wanted a happy ending—or at least a hopeful beginning for the rest of our lives. I wanted to box up the war and put it away. We had two children and a bright future. Let the pebble sink as the waters stilled.

But sometimes the ripple becomes a wave that threatens to sink the whole boat. PTSD, I learned, can be chronic and episodic. Brian had good weeks, months, years—but they were never permanent. He drank, sometimes heavily, when times were bad. Eventually, I reached a breaking point. I decided the status quo could not endure.

On Aug. 24, 2018, I took the metro back from work. Walking home from the station, I saw emergency vehicles in front of my house. Heart pounding, I walked inside. Brian sat in a chair by the door, where a paramedic assessed him. My husband was shirtless, covered in sweat, and confused. When I asked where our children were, he replied, “Children?”

I sprinted through the house. Our two children were nowhere to be found. I returned to him and asked, louder, “Where are our kids?!” He looked baffled. From the door, a tiny, nervous voice, our neighbor: “I have your kids.”

“How are you so calm?” she asked me. What else could I do? I wondered to myself. Was there any other choice? Out loud, almost automatically, I told her, “It’s from being in the military.”

My assumption was that Brian had had an anxiety attack, hyperventilated, and passed out. With PTSD, panic attacks were, for him, not uncommon. But the paramedic was concerned about how high his pulse and blood pressure were, as well as his ongoing confusion, so he was transported to the ER by ambulance, while I followed in my car.

After a couple of hours of waiting to be seen in the emergency room, Brian mentioned a pain in his shoulder. Given how long it took for the ache to begin, I guessed it was just bruised from his fall. Still, he asked the doctor for an X-ray. After what seemed like a further interminable wait, we learned he had had a seizure and had broken his collarbone when he fell.

There is a part of me that wants to distance myself from all of this by reverting to the safety of clinical terms. I want to revise these paragraphs and tell you I came home that day and my husband was diaphoretic and postictal. These words—dense, precise, diagnostic—come easier than remembering the specifics of my daughter retelling the story of daddy screaming and falling down in front of her for weeks as she worked through her own trauma. I want to write, of my husband, “He had been struggling for years with comorbid PTSD, major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, and TBI,” rather than ever admit the terror I felt during specific incidents, the embarrassment when the police came, the shame of pretending everything was fine when it definitively was not.

In the warped way that life sometimes unfolds, the horror of this incident ended up saving our marriage. Perhaps the ripples, now waves, had ricocheted off a rock—rather than swamping our tiny boat, they had pushed it away from the rapids. After the civilian ER doctor put Brian on an anticonvulsant known to cause suicidality, his Defense Department neurologist prescribed him a different anticonvulsant that was also a mood stabilizer. Things changed dramatically. What had been wild and frightening swings from sadness to rage settled into normal currents of emotion. When the doctor told him alcohol “reduced his seizure threshold,” Brian quit drinking. Sobriety became its own salve.

Time passed, the ripples spread. Even after 15 years. It had not occurred to me, when I walked into our house in 2018, that Brian could have had a seizure, because it had been 15 years since shrapnel gouged a trough in his brain just below the skull. After it happened, in 2003, providers had warned us about the risk of seizures post-TBI. But it had been 15 years without one.

For years, I had tried to convince myself that the ripples had been contained—that they had not spread beyond his parents, me, the Defense Department, and VA. Then, suddenly, our county had to send paramedics into our home. Our neighbors had to help run errands, since the state (rightly) banned Brian from driving for six months, until a doctor could affirm that his seizures were controlled by medication and it was safe for him to drive again. Our school system needed to provide counselors for our children. My employer had to give me extra time off work to drive him to medical appointments.

There are now more than 1.9 million U.S. veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. More than 50,000 of us were physically injured. Around 15% have experienced PTSD. And perhaps all of us were exposed to burn pits and other toxins, as were an untold number of Iraqis. The long-term impacts of the war on frontline civilians and third-country nationals have barely been considered. I am just telling you our story, my husband’s and mine. Ours is but a tiny ripple, from a single pebble, in an ocean.

My generation has benefited tremendously from Vietnam veterans, who fought like hell to get PTSD recognized. Because of their tenacity, we finally have a language to describe, and evidence-informed treatments to manage, the psychological effects of the trauma of war. And like Iraq veterans, Vietnam veterans also struggled for decades to get recognition of the impacts Agent Orange had on their health, of its risks to their children. After we started coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan, they swore, “Never again,” and fought alongside us for a swifter and better response to our own toxic exposures.

This advocacy recently led to passage of the PACT Act, which adds a dozen different cancers and another dozen illnesses to the list of health conditions VA assumes (or “presumes”) to be caused by exposure to toxic substances for all who deployed to Afghanistan, Iraq, and other qualifying locations after 9/11 or during the first Gulf War—as well as adding new conditions to the list of illnesses assumed to be linked to Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam veterans. VA has already screened more than a million veterans under the new program, hiring 2,000 new disability claims processors and additional health care providers to manage the influx of new patients and claims.

As a veteran and a caregiver, I am profoundly grateful to all who advocated for this expansion—even while, as a taxpayer, I blanch a bit at the projected price tag of $152 billion over the next 10 years for disability compensation alone. And I know the PACT act may still not capture all conditions. Cancers often take decades to develop. The potential epigenetic effects of our exposure, passed on to our children and grandchildren, may take generations to identify.

The ripples may yet become waves: PTSD has been linked to heart disease; TBIs are associated with dementia; caregivers are at increased risk of hypertension, reduced sleep, and mental health problems.

And the ripples from this 20-year-old war will long outlive me, spreading for many decades to come. In 2020, Irene Triplett died, age 90, the last surviving dependent of a Civil War veteran receiving a pension, 155 years after that conflict ended. Life expectancy has only increased since the Civil War ended in 1865, or since she was born, in 1930. Brown University’s Costs of War project estimates $2.2 trillion in federal obligations for post-9/11 veterans’ care over the next 30 years alone—this number does not include costs that cities, counties, and states bear as well.

When we project the costs of war into the future, we must imagine these collective costs, these ripples, that will continue spreading for at least another 155 years. It is daunting to imagine that somewhere among the cohort of Iraq War veterans is likely a man who will father a child well into his old age, who will live for many years, and that there could be another, similar headline to that about Triplett’s passing, in the year 2166 or beyond.

As the anniversary of the Iraq War approached, and of the day I crossed the berm two days later, I have not been looking back to the start of the war, but forward—to where the ripples are likely to go. What I’ve come to realize is this: They’ve only just begun to spread

This War Horse reflection was edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

By Kayla Williams. Kayla Williams served as a sergeant and Arabic linguist in the Army from 2000-2005, including a deployment to Iraq from 2003-2004. She now lives in Virginia with her husband and two children and works as a senior policy researcher at the RAND Corporation. She’s the author of two nonfiction books, Love My Rifle More Than You and Plenty of Time When We Get Home. Williams is a 2018 War Horse Fellow.

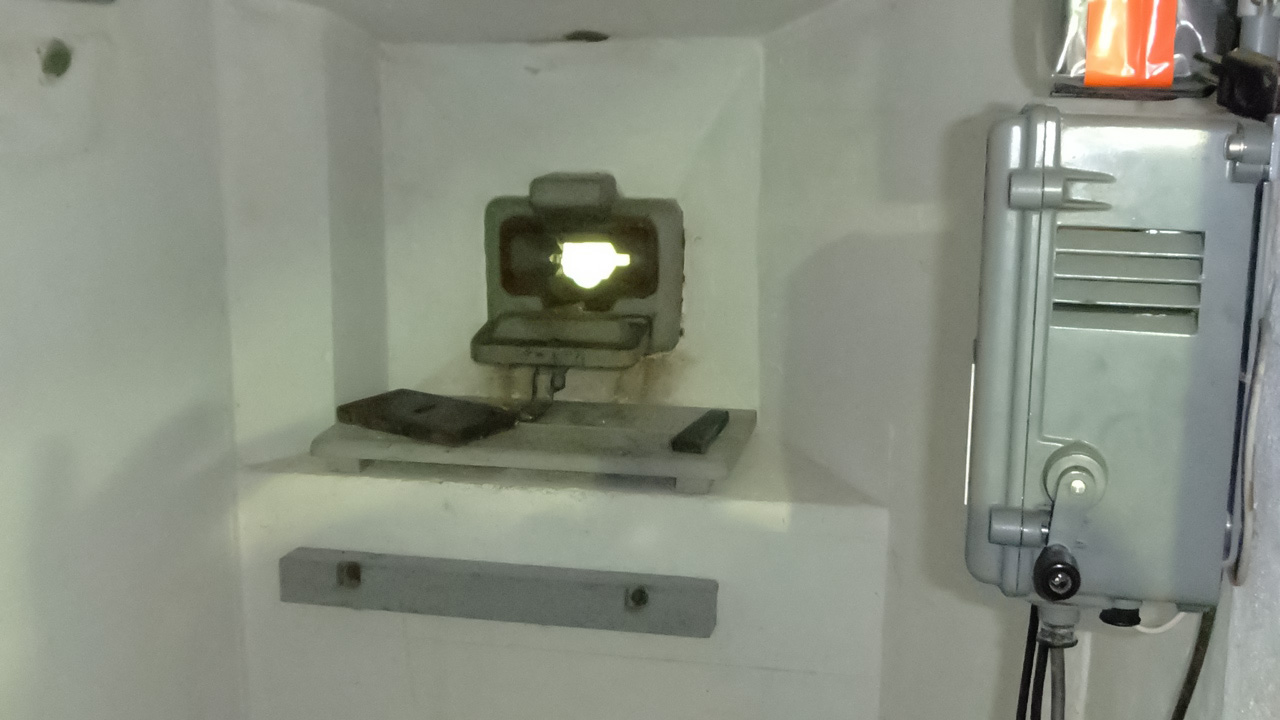

In addition to the National Redoubt, Switzerland also had a vast network of underground tunnels, many of which were connected to the country's extensive railway system. These tunnels were used to transport troops, supplies, and equipment during the war.

In addition to the National Redoubt, Switzerland also had a vast network of underground tunnels, many of which were connected to the country's extensive railway system. These tunnels were used to transport troops, supplies, and equipment during the war. Nevertheless, the country's extensive bunker system remains a testament to Switzerland's obsession with national defense during one of the most turbulent periods in modern history which is now almost glamorous compared to today's global geopolitics and the imminent threat of multiple nuclear wars.

Nevertheless, the country's extensive bunker system remains a testament to Switzerland's obsession with national defense during one of the most turbulent periods in modern history which is now almost glamorous compared to today's global geopolitics and the imminent threat of multiple nuclear wars.